‘A rather imposing three-story brick building’

An illustrated history of the Cascade Saloon

We may never know who first built a structure at what is now 408 S. Elm Street. And even if we did, we might never know why they chose to put a building in such an awkward spot between two railroad tracks. But a building may have been there as early as 1879, when the city directory listed a “billiard saloon” on the west side of South Elm Street, in the first block block south of the railroad tracks (street addresses were not yet in use). The business was operated by Walter Allsup, an engineer on the Roanoke & Danville Railroad.

An 1885 Sanburn fire insurance map shows a long, narrow building between the railroad tracks at what eventually would be known as 408 South Elm Street. It’s divided into two sections, identified with “Sal” at the front, suggesting a saloon, and “tenemt” at the rear suggesting apartments. The 1884 city directory showed at least one resident living at “S. Elm and R.& D. R.R.”

The earliest known owner of the property was Seymour Steele (1830-1883), a prominent businessman of the 1870s. It was one of many properties he owned when he died. Steele sold groceries and clothes and was co-owner of a sash, door and blind factory nearby. In the early 1880s he operated the Central Hotel at Market and Elm streets. He was the founding treasurer of the Greensboro Building & Loan Association in 1870, a town commissioner and board member for Greensboro Female College.

In 1887, Samuel Johnson McCauley (1847-1930) bought the property from Steele’s widow, Mary. McCauley’s wine and liquor store appeared in the city directory that year at 408 S. Elm Street, the first time the address was listed. The business was identified as a saloon the next year.

In 1895, McCauley had a larger brick building built around the frame structure. The new building had two storefronts, 408 and 410 S. Elm. In 1896, J.C. Olive & Co., a wholesale grocer, occupied 410. It was the first of a long series of retail and wholesale grocers in the building. The area was crowded with grocers. The 1898 city directory shows 15 on South Elm Street, including J.C. Olive at 408 and seven in the 500 block. There were four more nearby on Lewis Street.

The Greensboro Patriot,

August 7, 1895

The 1885 Sanburn map showing a building much narrower than the 1895 building, between the railroad tracks on South Elm Street, just south of the Roanoke & Danville Railroad freight depot.

1890 city directory

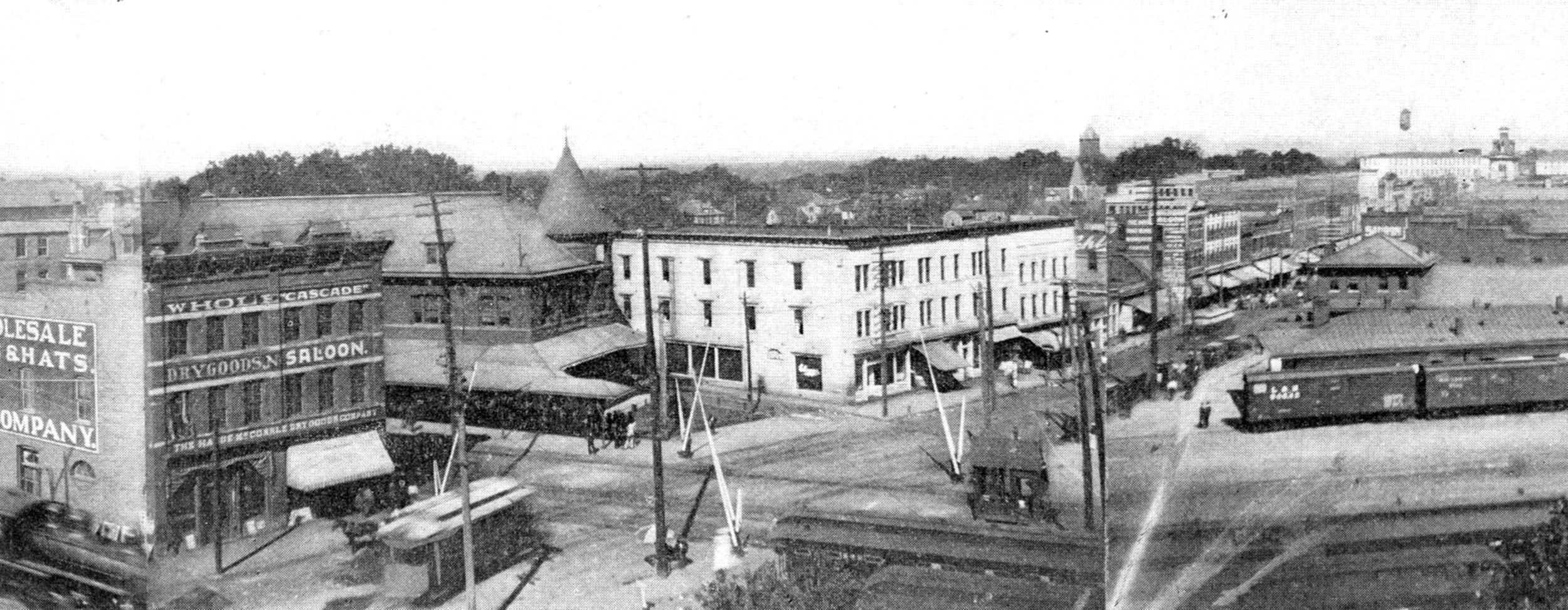

1900 (Photo courtesy of the Greensboro History Museum)

1896-1930: The busy years

By 1901, McCauley had moved the saloon to 366 S. Elm. From 1901-04, Hague-McCorkle Dry Goods appears to have occupied the entire building. The Greensboro Telegram called it “a rather imposing three-story brick building” and found it “unusually well adapted for the business, being roomy and well-lighted from all sides.”

408 and 410 S. Elm were vacant in 1905. The building wasn’t listed as vacant again for decades, but it’s likely that there were many years when it was partly or even mostly empty. As many as five businesses were listed some years, only two in others. Some used rear entrances; some were listed at 410 1/2 S. Elm.

One of the most notable early tenants was Wiley Weaver’s eating house from 1907 to 1910. Weaver and his wife, Ida, were African Americans operating a restaurant in white downtown Greensboro during the Jim Crow era of racial segregation.

Long-term tenants in the building’s early days included the Cascade Billiard Parlor in 410 1/2 from around 1913 to 1924; the proprietors also operated the Atlanta Wienie Stand No. 1 in 410. The Central Cafe from 1915 to 1924 was the first of three cafes with that name. It closed not long after the owners were busted for possession of liquor during Prohibition. The W.F. Clegg Cigar Company produced its General Greene and El Edisto cigars in the rear of the building from 1921-31. Citizens Coal Company had the longest tenure, operating in the rear of 410 from 1925 to 1956. Other businesses moved in and out — among them, restaurants, grocers and building-trade firms, including roofers, a cabinet-maker and a heating company.

1928 city directory

Greensboro Daily Record,

August 25, 1924

Greensboro Telegram,

April 20, 1901

1930-1974: A long, slow decline

After McCauley died in 1930, his family retained ownership until 1946, when Christopher H. Kypris bought it and opened a restaurant in the building. He apparently lost the building in a foreclosure two years later. It was bought then by restaurateur Charles I. Eways (1909-1978). He owned the building for 20 years but continued to operate his restaurant on East Market Street.

A variety of businesses occupied the building, mostly for rather short stays. Another Central Cafe operated from 1929 to 1943. At least four grocers were in the building at various times, in addition to an antiques store, a chicken hatchery and feed store, a furniture-repair business and a warehouse. The last restaurant, a regular feature of the building for 35 years, closed in 1950.

Gate City Produce (1953-66) and Baker Furniture (1959-1968) were the longest-operating businesses in the later years. By 1960 they were the only tenants, and after 1966 only Baker was listed. As downtown declined, the Cascade Saloon’s fortunes faded as well. A series of furniture salvage stores came and went through the 70’s.

Greensboro Daily News, October 25, 1961

Greensboro Daily News, January 23, 1956

1974-2014: Neglect and deterioration

In 1974 the building gained its most high-profile, and problematic, owner, attorney Ross Strange. He initially moved his weekly newspaper, The Greensboro Times, into the building. By 1980, the newspaper was gone, and so was the last furniture-store tenant. For the first time in 75 years, the building was vacant. No business occupied it again. Strange used it for storage. By 1988, the city directory stopped even listing the address.

Strange had served as District Court prosecutor from 1968 to 1970. He made headlines across the state in 1970 when he had the manager of the Janus Theatre arrested for showing “I Am Curious, Yellow.” He called the film not only obscene but also “communistically inspired.” A judge disagreed, acquitted the manager and allowed the film to be shown.

Between 1963 and 1974, Strange ran for City Council, District Court judge (twice) and district attorney. He lost all four elections. In 1971 he bought the venerable Embassy Club in Sedgefield, “the South’s most exclusive” nightclub, its ads said. It burned down in 1976; the cause was never determined. Strange said he would rebuild it, but didn’t.

Under Strange’s ownership, the Cascade Saloon steadily deteriorated. Water leaking from a decaying roof devastated the interior, and the building appeared ready to collapse. In 2001, the city began pressuring Strange to fix the building, sell it or tear it down. He refused to even let city inspectors in. They entered on their own and found a dangerously unstable building. The fire department declared it too dangerous to enter if it burned. For 13 years, the city struggled with Strange, who was determined to neither fix nor sell the building. Finally, the city used eminent domain to take ownership in 2014 and turned it over to the Preservation Greensboro Development Fund to find a buyer.

News & Record, July 20, 2015

2015 to Today: Transformed

It had taken more than 10 years to rescue the building. Its condition was so desperate that some engineers and developers said it couldn’t be saved. Yet, it took only a year for the Fund to find a buyer with the expertise and commitment to restore it. In 2015, the Christman Company, a construction firm based in Lansing, Michigan, took on the Cascade Saloon to be its new regional office. Christman was experienced in historic restoration and appreciated the history of the building.

“Renovations to the three-story building located at an urban crossroads presented significant technical challenges to the construction team,” the company says in its account of the project. “Operating between two busily functioning railroad tracks adjacent to the site, stabilization of the historic masonry structure, working with extremely limited space for construction materials and deliveries, and replication of the historic exterior cornice were just some of the key project challenges that the team overcame. A construction approach of ‘building a ship in a bottle’ was used to erect a new support structure inside the historic brick walls.”

Christman’s $4.2 million restoration was completed in 2018. It received financial support from City of Greensboro, Downtown Greensboro Inc. and the Marion Stedman Covington Foundation. State and federal tax credits also helped make the restoration possible.

Contractors on the project included Tise-Kiester Architects; Bennett Preservation Engineering PC, structural engineer; Kuseybi Engineering PLLC and Consultant Engineering Service, mechanical engineers; Dan Campbell Engineering, P.A., electrical engineer; and Borum, Wade and Associates, P.A., civil engineer. Christman served as construction manager.

The completed project received awards from Carolinas Associated General Contractors, the National Association of Women in Construction and Preservation North Carolina.

The Cascade Saloon is a contributing structure in the Downtown Greensboro Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places. It has been designated a Guilford County Historic Landmark.

News & Record, September 13, 2012

News & Record, April 7, 2014

News & Record, January 20, 2005

News & Record, February 15, 2013